Australians are voting in their first referendum regarding First Nations people since 1967. Winning 93% of the vote, the 1967 Referendum was the most successful in Australia’s history. Throughout the 2023 referendum, some have expressed uncertainty over the legal impact and implications of the Voice.

We spoke to Associate Professors Elisa Arcioni and Andrew Edgar of the University of Sydney Law School to gain clarity over how the Voice came about, what it can (and can’t) do, and what legal practitioners need to know about the Voice.

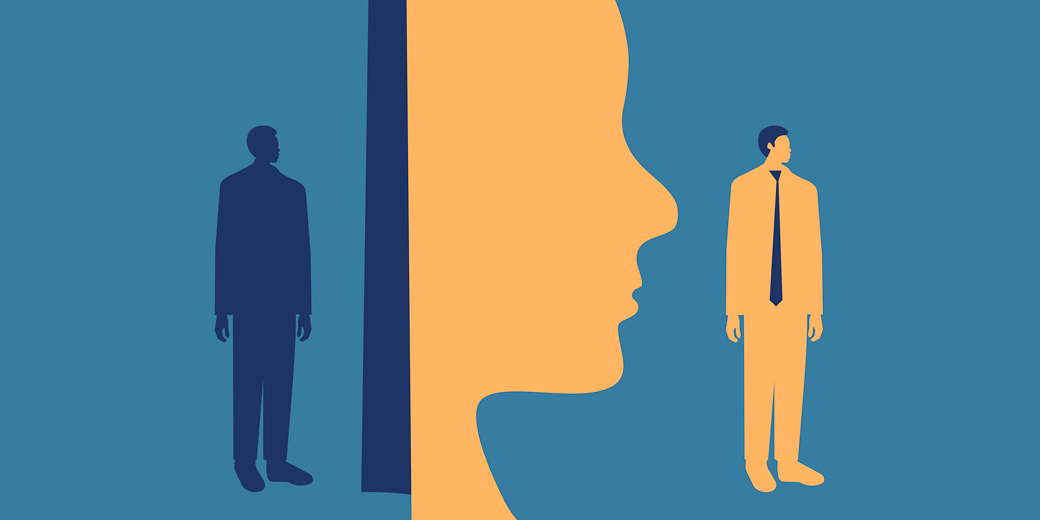

The Voice won’t exercise legal authority. It provides advice only.

“There will be a new institution called ‘the Voice’, and it will have an advisory role only,” Associate Professor Elisa Arcioni explains. “It will not exercise legal authority or make decisions. The Voice would interact with the existing structures of government, the Parliament and the Executive, but its function is advisory only.”

Since Australia’s colonial era, there have been calls for First Nations people to have a voice in the law and policy that affects them.

“This came in various forms, from petitions to the monarch, to government, or calls for representation in Federal Parliament,” Elisa says.

Over time, this transformed into a discussion over constitutional recognition.

“The Uluru Dialogues sought to achieve a representative sample of what First Nations people wanted from constitutional recognition. This led to the Uluru Statement from the Heart. They made it very clear - they don’t want symbolic recognition. What they want is recognition through a Voice.”

Legally, it’s a modest proposal consistent with our system of government

According to Elisa, the Voice achieves a combined function of providing explicit constitutional recognition to First Nations people, and a formal body to advise Parliament on law and policy that affects them.

“Legally, it should be understood as a very modest proposal, because it does not exercise legal power or authority,” Elisa says. “The aim is for the Voice to give advice to Parliament and government, with the hope that they will listen and take their advice into account. But they can’t force the Parliament and Government to do so.”

Elisa describes the proposal as ingenious for a number of reasons.

“It’s ingenious, in a way, because the Voice is completely consistent with our system of representative and responsible government. Australia’s representative parliament and responsible government have legal power, but are required to exist at the same time as the Voice, an advisory body that can speak, but not force existing institutions to do anything in particular. The Voice fits within our system, but is unique and distinct, so as to respond to the historical lack of political power experienced by First Nations people.”

Parliament retains a lot of control

Associate Professor Andrew Edgar specialises in Administrative Law. In this field, he’s seen some argue the Voice might encourage an influx of litigation.

“I don’t really see how this would be the case,” Andrew observes. “Administrative Law is primarily focused on decision-making and processes established by Acts rather than by the Constitution.”

The Referendum merely provides for a constitutional amendment to recognise an advisory body reflecting First Nations people. How the Voice would operate on a day-to-day basis was always the purview of Parliament.

“I think what’s often missed in this debate is that Parliament will have a lot of control over the legislation,” Andrew explains. “As administrative lawyers, we would recognise that there is a lot of scope to make legislation in a way that can facilitate litigation, or not facilitate litigation.”

“Arguing about the risk of a lot of litigation is just premature,” Andrew says. “This will be dependent on what’s in the Act. This is the main point that hasn’t really been a bigger part of the debates – I mean, administrative law doesn’t usually end up in big public debates!”

You can design the law to diminish the risk of litigation

Andrew points out that Australian law already features Commonwealth Acts that empower administrative officials to make decisions relating to Aboriginal people.

“If you look at our current situation, there is no great flood of administrative litigation from Aboriginal people,” Andrew says.

According to Andrew, it is also possible to design the legislation to avoid the risk of litigation.

“They might design the legislation so that the Voice is filtered through the political system, and in this way, avoids the risk of litigation,” Andrew observes.

What if you’re asked to explain the Voice?

“What the debate of the past few months has shown is that there remains very low literacy about how law and politics operate in Australia,” Elisa says. “Australians don’t always understand how powers are distributed across the legal system.”

Unfortunately, some have seized on this to sow false claims.

“Some key claims based on false statements have really gained traction,” Elisa continues.

As legal practitioners, you might be asked to explain the Voice to clients, friends or family.

“I encourage lawyers to reflect on their knowledge of the basic elements of the legal system, and to think of the Voice in that context,” Elisa says. “It’s an institution that will exist within institutions they are already familiar with and engage with in their practice. It’s something new, but it’s not an alien being. It coexists with our existing structures of government.”

For those baffled by the conflicting messages of the Yes and No campaigns, Elisa counselled common sense.

“Think about who are making these claims in the media, why they might be saying them, and try to seek a source of information that is trustworthy,” Elisa says.

“Regardless of the outcome, it’s clear there is a need for legal academics and legal practitioners to help people understand our legal and constitutional history, how power is exercised, by whom and within what limits. Once you have that foundation, you can actually move forward to think about what might be solutions for social problems,” Elisa says.

Any uncertainty can be managed within Administrative Law

“To me, there’s nothing necessarily politically partisan about this issue,” Andrew says, especially as there was talk of bipartisan support earlier this year. “I’ve found it surprising this debate has gotten so heated.”

Some have claimed the Voice will lead to uncertainty.

“There’s a fear around the idea that we don't know how this is going to work,” Andrew says. “So there’s uncertainty about this.”

“By its very nature, administrative law can be an unclear, uncertain area of law,” Andrew explains. “This is because it depends on interpreting different Acts. Often the Acts are not too clear about exactly what must be considered in an administrative decision. So I can see how uncertainty extends into fear.”

However, Andrew believes uncertainty can be managed.

“You can design Acts in all different ways,” Andrew continues. “We’ve had centuries of designing Acts, and establishing decision-making institutions and processes. I think any uncertainties can be managed without too much difficulty. As administrative lawyers, we have all the tools we need.”

The People decide on the principle, while Parliament determines the details

What we’re being asked by the referendum is a question of principle. As voters, Australians are being asked whether or not Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be recognised through a Voice to Parliament.

“It’s then for Parliament to determine the details about the composition, functions, powers and procedures of the Voice,” Elisa explains. “This is standard when you set up institutions in the Constitution. You guarantee the core functions of an institution, and defer the detail for Parliament to determine. It’s not just some random individual or self-interested, partisan body. It’s our representative Parliament whose job it is to determine the details.”

It’s a distinction Elisa finds herself reiterating often at sessions about the Voice.

One analogy she makes is the fact that Parliament - not the Constitution - determines who its electors are.

“We know from the Constitution that members of Parliament are to be directly chosen by the people. However, the Parliament has the power to decide who those people are,” Elisa says. “I would not want that kind of detail in the Constitution. Given when the Constitution was written, if that detail had been entrenched in the Constitution I would not be able to be an elector, because I’m female and a majority of colonies did not enfranchise women at the time. That’s why you leave those kinds of details to Parliament for ongoing flexibility and change.”

Flexibility and change means the Voice can always speak

“You will have some more generous parliaments that might give greater leeway to the Voice as to what they can do, how they can do it, and what impact their representations might have,” Elisa says. “But if the nature of the Australian community changes, you may have a Parliament (which is representative of the people) limit what the Voice can do and how they can do it, and what impact it has.”

“What constitutional entrenchment means is that you can never get rid of the Voice,” Elisa explains. “The Voice can always speak, but the impact of the Voice will actually track with the community because the Parliament will make the decision about what impact the Voice will have. It will be consistent with the general politics of the community over time, and that will likely change as the composition and nature of the community changes.”

![How to handle Direct Speech after Gan v Xie [2023] NSWCA 163](https://images4.cmp.optimizely.com/assets/Lawyer+Up+direct+speech+in+drafting+NSW+legislation+OCT232.jpg/Zz1hNDU4YzQyMjQzNzkxMWVmYjFlNGY2ODk3ZWMxNzE0Mw==)